- There is much debate about who were the Malay Peninsula’s original inhabitants, made more heated by the ‘sons of the soil’ status Malaysia gave Malays

- Many Malaysians think of Chinese and Indians as having arrived under colonial British rule, but some Indians claim a history going back 2,500 years

History is the version of past events that people have decided to agree upon, Napoleon Bonaparte once said. In Malaysia, such an agreement is not easily come by.

The issue of historical narrative blew up again in July last year, when newly appointed human resources minister M. Kulasegaran found himself in hot water with the Malay majority by claiming the country’s Indian ethnic minority were among the original inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula.

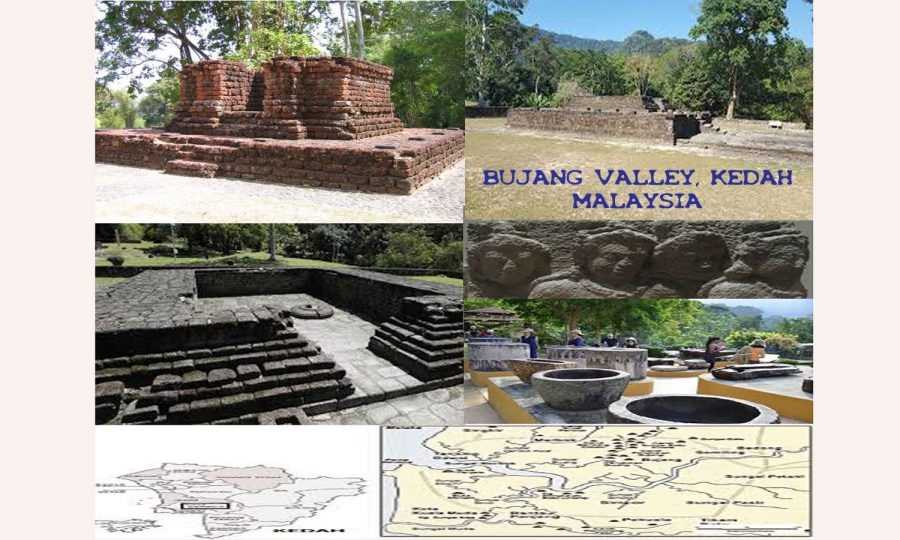

In his speech, which was uploaded to YouTube and went viral, Kulasegaran cites Kedah state’s Bujang Valley, with its ancient Hindu temples, as proof of Indian presence on the Malay Peninsula more than two millennia ago.

“Many people will say our history started 120 to 130 years ago. That is wrong. We came here 2,500 years ago. The evidence is at Bujang Valley,” he says in the video.

What sparked the bigger uproar was Kulasegaran’s assertion that Malays are the pendatang, or newcomers. “We are equal. This is our homeland,” he said.

The minister later apologised for his remarks, saying he had only been making the point that it is unfair to describe Malaysia’s Indian citizens as pendatang.

A lot of the rhetoric surrounding immigration these days tends to be directed at people who fit this same description – new arrivals – such as those fleeing war-torn countries in the Middle East and Africa, or Myanmar’s Rohingya, despite the latter’s presence for generations in that country.

In Malaysia, however, “immigrants” is a word often used not to refer to newcomers at all, but levelled at those whose families are perceived, rightly or wrongly, to have arrived in the country more than 60 years ago, during British colonial rule.

Many ethnic Indian and Chinese labourers were shipped in by the British to work in mines and plantations. They were granted citizenship when Malaysia’s founding fathers laid the groundwork for independence in 1957. The ethnic Malays and indigenous tribes, on the other hand, were granted bumiputra (sons of the soil) status, enshrined in Article 153 of the Malaysian constitution.

This gave them special privileges, such as preferential access to education, scholarships, public services and facilities.

This “social contract” fails to acknowledge the descendants of Indian and Chinese merchants who arrived long before Europeans set foot on the peninsula, however. It serves as a constant reminder of the difference in status, and the thorny issue of who is and who is not an immigrant.

According to historians, Bujang Valley – the ancient site at the centre of the debate – was a trading hub at the heart of maritime Southeast Asia for merchants sailing between China, India, Arabia and the Malay Archipelago.

Along a sea route that served as an alternative to the maritime section of China’s ancient Silk Road, the area grew prosperous and is referenced in Chinese, Arab and Indian literature. The valley was a centre for Hindu and Buddhist culture, as is evident by the many excavated temples.

The adoption of religious, cultural and political references from ancient India in Southeast Asia, believed to date from the 3rd to the 12th centuries, led scholars to coin the term “Indianisation”.

Kulasegaran was not the first person to dig up the issue of Indian origins in Malaysia last year. In a theatrical production in April, Parameswara, the founder of the Malacca Sultanate, in what is now the state of Malacca, was depicted as, and played by, an Indian.

Historians, meanwhile, recognise the 14th century prince, originally from Sumatra in modern-day Indonesia, as a Hindu Malay.

In what was seen as a response to Kulasegaran’s speech, in October the National University of Malaysia’s Institute of the Malay World and Civilisation organised a forum entitled “Polemics of Indian presence in the Malay Peninsula: Migration or Immigrants?”.

The event drew flak from the Indian community, particularly since all four panellists were ethnic Malays.

Indian students at the university objected to the forum, leading a state politician to suggest that the participation of non-Malay academics would calm the waters. In an attempt at damage control, the university changed the name of the forum to “The population and ethnic movements in the Malay Peninsula from the perspective of archaeology, culture and history”.

V.S. Maniam, an ethnic Indian NGO worker who attended the forum, is firmly of the view that Indians have been living on the peninsula since at least 1025, the year Rajendra Chola, a Tamil king from southern India, sacked the cities of the ancient empire of Srivijaya.

“When the Chola king came [his dynasty] ruled Southeast Asia for 500 years. That is on record; we have evidence of it. But most of the artefacts have been destroyed in this country, even in Bujang Valley,” he tells the Post.

“It has been said that we [ethnic Indians] have not done anything for the benefit of the people. They treat us like dirt,” Maniam says.

The temples in the Bujang Valley were built by the Chola king for iron smelting, he insists. “No denying it. I have the facts in history books,” Maniam adds, citing A History of Malaya and Her Neighbours (1957), by F. J. Moorhead.

Dr Zuliskandar Ramli, an archaeologist from the National University of Malaysia and one of four Malay panellists who took take part in the forum, refutes Maniam’s claims. He suspects Maniam’s views are influenced by the “Greater India colonisation theory” penned by Bengali scholars in the 1920s.

“The terminology of Greater India was popularised to instil Hindu nationalism. Journals published by the Kolkata-based Greater India Society mention the spread of Indian influence in Southeast Asia, China and Japan,” says Zuliskandar.

He credits British researcher H. G. Quaritch Wales for introducing the theory to Southeast Asia in 1935.

Zuliskandar also claims that artefacts excavated at Bujang Valley differ from those found in India, because Bujang artisans did not strictly adhere to shastras, or manuals, as did Indian artisans.

In 1974, Zuliskandar adds, Wales had a change of mind and theorised that the valley’s structures were a result of acculturation.

“The local Malays borrowed Indian traits they favoured and adapted them to their animistic beliefs. Earthenware excavated in the valley also exhibits local craftsmanship,” he says.

P. Ramasamy, a leader of the Democratic Action Party in Penang state, himself ethnic Indian, says the issue of Indian origins at Bujang Valley has surfaced as a result of misunderstandings based on partial knowledge. He urged ethnic Indians to accept the “fact” that they were not the first settlers of the Malay Peninsula. Historical facts, says Ramasamy, are the province of historians.

So what caused the origins issue to resurface in public discourse, and can the argument be resolved by mere facts?

“To have the facts is one thing, but managing facts is another,” says Dr Ahmad Murad Merican, from the Centre for Policy Research and International Studies at Malaysia’s University of Science.

Non-Malays have long held a revisionist attitude towards the country’s “official history”, but have not always aired their views publicly, he adds.

“The cracks appeared during [Abdullah Badawi’s] time as prime minister [2003 to 2009], during the rise of the internet, which provided people with a medium to express their identity more.

“Back in the 2000s, there was a ‘crisis’ in the formation of the history syllabus for school textbooks. History textbooks were criticised for being biased towards the Malays and Islam, while at the same time neglecting the role played by non-Malays,” Merican says.

“What we are seeing is that they want to claim their history … to stress that they were involved in the nation-building process. In the process of asserting themselves, they also accuse the Malays [of] being pendatang.”

The history of Malaysia, it appears, is perceived through an ethnic lens, with each race seeing it from their own perspective.

Merican says it is important, first and foremost, for Malaysians to recognise that there are many narratives – or histories – in Malaysia.

“Secondly, we must have continued engagement [between races]. Thirdly, establish a tribunal to mitigate the issue, and as time goes on we hope Malaysia as a nation state accepts various interpretations of history based on evidence and facts,” he says.

Ahmad Mustakim Zulkifli – 19 Feb, 2019 – Source: https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/article/2186591/who-arrived-first-malay-peninsula-depends-whether-youre-indian-or-malay